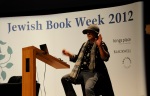

Jeffery Goldberg spoke to Robin Lustig on Israel After the Arab Spring at JBW on Sunday 26th February. You can view a video of the conversation here.

Jeffrey Goldberg’s writing on the Middle East in the Atlantic and elsewhere, is invariably incisive, principled and memorable. And he carries serious clout. Five days after his Sunday morning session at Jewish Book Week, it was Goldberg who secured Barack Obama’s longest interview to date on the subject of Israel, the US and the Iranian nuclear programme.

And if he’s enjoyable in print, the same is true in conversation, this time with the presenter of Radio 4’s the World Today, Robin Lustig. Introductions done, Lustig read a quote. “I salute all the nations of the Arab Spring and I salute the heroic people of Syria who are striving for freedom, democracy and reform.” The quote was from a speech by Gaza’s Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh, delivered during the previous Friday’s prayers at Cairo’s Al-Azhar mosque. What do you think this means for Israel? Asked Lustig. “Is it good for the Jews?” quipped Goldberg. More than what it means for Israel, he went on, is what it means for Assad. And for Assad, he said, “Ismail Haniyeh is the fat lady, and the fat lady has sung.” (I enjoyed Goldberg’s characterisation of Haniyeh as a singing fat lady. Partly as I doubt the burly terror chief welcome either the reference to his weight, or his feminisation, and also because, according to Palestinian news reports, Haniyeh’s junta banned fat ladies, thin ones, or men of all weights, from singing in Palestinian TV’s version of the X-Factor.)

And what about the potential if horrifically bloody fall of Assad? Good for Israel? Asked Lustig. “Good for humanity” replied Goldberg. And strategically, given that Assad’s Syria is Iran’s only Arab friend. And while in Egypt, Mubarak “kept a lid on things”, for decades the Assad family had used Lebanon as a proxy for its war on Israel. “No one’s sitting shiva for Bashar,” he concluded.

Lustig then posed a question that we should get used to hearing more. An Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood leader had told him Israel was “no longer the only democracy in the Middle East.” Goldberg was dismissive. “I don’t think the Muslim Brotherhood’s intentions are democratic… And they’re getting ahead of themselves” he said, pointing out the ongoing control of Egypt’s military. The test for the Muslim Brotherhood would not be the first but the second election. “One man, one vote, one time”, interjected Lustig. We need to wait and see what happens once they and the Salafi Al-Nour party who also won an alarming percentage of votes in Egypt, are responsible for garbage collection as well as grandiose ideological plans.

Israel’s status as the Middle East’s only democracy was one of its unique selling points in the West, he added, before raising concerns with “moves afoot by Israel’s rightwing parties,” that he felt undermined those principles.

Moving back to the Arab uprisings, Goldberg stated, “This is not an Arab Spring but a Sunni Islamist awakening” and the Muslim Brotherhood were hiding their real agenda. But they’re pragmatists, cautioned Lustig, who look to Turkey as a role model and recognise the need for economic growth and tourism. Goldberg agreed that economic necessity was the greatest check on Brotherhood ideology, before adding pointedly that when it came to relations with Israel, Turkey was scarcely a model to emulate.

Looking at the bigger picture, he reflected that since the Iranian Revolution the Gulf region has seen near constant turmoil, while investment in the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel has been incredibly cost effective. Which brought him onto Iran. Yitzchak Rabin, he argued, embarked upon the Oslo process because he foresaw the Iranian issue. Rabin wanted to make peace with the Palestinians and the Arab world because he recognised a strategic imperative to form a united front against Iran. Given the number 1 spot Iran continues to occupy in Israel’s strategic priorities, Goldberg was flummoxed by what he saw as “lack of effort” on the part of the current Israeli government to do more to pursue the peace process, and in turn, build a more effective regional coalition against Iran. And, he said, the Obama administration had been a bit flummoxed too.

But even in his criticisms of Israel, Goldberg was mindful of its challenges and dilemmas, mentioning the bitter experience of previous attempts to make progress – the withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, the disengagement from Gaza in 2005, and the missiles and painful military campaigns that followed both.

One thing the Arab Spring had done, both Goldberg and Lustig agreed, was undermine the notion that solving the Israeli-Palestinian dispute could be a panacea for all the ills of the region. That said, “I read the Guardian and it seems like Israel’s still the big problem,” joked Goldberg to appreciative guffaws from the audience, He recalled a Kurdish leader who had once told him, “I wish our enemies were the Jews. Then people might pay attention.” But the most volatile split in the region, he added, is not between Jews and Muslims but between Sunnis and Shias.

Are dictatorships better for Israel than fluid, unstable, Islamist states? Asked Lustig. Short-term yes, long-term, and ethically, no, came the reply. People want to be free, but the path to real democracy will be a “long and unpleasant ride” that “takes a detour through Khomeinism.” Ultimately, he predicted that “when the people realise that Islam might be a spiritual solution but not a political solution, that’s when we’ll see the real transition to democracy.” But dictatorships can’t keep a lid on it forever.

Questions followed. On the Palestinians, Goldberg imagined an equivalent of Gandhi’s Salt March on a big Jewish settlement, and wondered how Israel could possibly cope with that, while acknowledging that “sometimes the Palestinian version of non-violence includes rock-throwing.” But there’s the thing – “where’s the Palestinian Mandela? If Arafat had been Mandela there’d have been a Palestinian state years ago.”

On the Iranian question, Goldberg stated with certainty that “one week from today, Obama is going to say “you don’t have to hit Iran because I will not let it go nuclear,” a pretty accurate prediction. Looking longer term, he pointed to the internal politics of Iran, and allowed himself the non-time specific optimism that “some time in the next 10 to 50 years, everything will be fine.” But, he cautioned, as long as there’s a critical mass of government militias prepared to slaughter their fellow citizens, then it’s very hard to overthrow a regime.

Of course, no session on Israel with a Jewish audience would be complete without the mandatory question on Israel’s PR. There’s no doubt, Goldberg suggested, that Israel receives disproportionate levels of attention with a large dose of double standards. He recalled being in Bethlehem during the second intifada, seeing an Israeli tank moving through the souq before coming to a halt in Manger Square and thinking – that’s not going to look good on the world’s TV. The fact is, he added, “Israel hasn’t gotten good PR since Jesus. We’re the parent religion of two daughter religions that have set themselves in opposition to the parent.” Having said all that, and having given an entertaining, thorough and historical appraisal of the inherent challenges in Israel’s PR, Goldberg added, “you still don’t have to act like a schmegegge